Odds & Ends

|

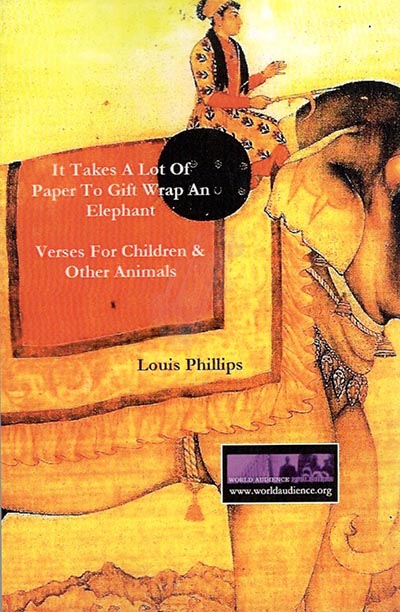

Writer: Louis Phillips

Artist: ShinYeon Moon

|

|

Writer: Louis Phillips

Artist: Jonathan Burkhardt

|

Quotations

Academy/Academia

Who killed James Joyce?

I, said the commentator,

I killed James Joyce

For my graduation.

— Patrick Kavanagh, from "Who Killed James Joyce?"

"...I have lectured on campuses for a quarter of a century, and it is my impression that after taking a course in The Novel, it is an unusual student who would ever want to read a novel again." — Gore Vidal

Adam

Adam was but human — this explains it all. He did not want the apple for the apple's sake, he wanted it only because it was forbidden. The mistake was not forbidding the serpent; then he would have eaten the serpent. — Mark Twain

Adultery

A lady temperance candidate concluded her passionate

oration, "I would rather commit adultery than take a glass

of beer!" Whereupon a clear voice from the audience asked

"Who wouldn't?"

— from THE RANDOM HOUSE TREASURY OF HUMOROUS QUOTATIONS, edited by William Cole & Louis Phillips

Humorous Verses

Of Keats & Cortez

Hernando Cortez —

Didn't Keats confuse him with Balboa, or was

It Desoto?

Hold it! One was an explorer; the other's an auto.

Carmen Miranda

Carmen Miranda

& I went out to the veranda

Where there was much more room

To chica-chica-boom.

Burnum Burnum

Phineas T. Barnum

Shd have met Burnum Burnum

Because Burnum might have earned Barnum

Many many dollars per annum.

George Washington Ferris

George Washington Ferris

Invented just for us

A wheel that goes round & around & round,

& when we get off, we kneel down, & kiss the ground.

Horace Greeley

Horace Greeley —

Did he really

Say "Go west young man"?

Or was it — "Go to Miami, young man, & get a tan"?

|

Children's Verses

Clouds

As long as I can remember

Clouds have been white.

If that fact is so,

Why can’t I see them at night?

Advice

The best advice that I can give

Is from a centipede’s mother —

Put your best foot forward

& then another & another & another

& another & another

& another & another

& another & another

& another & another

& another & another

& another & another

& another

The World Famous Eraser Poem

ERASER

ERASE

ERAS

ERA

ER

E

-

The Elephant

Of all the facts about mammals

This is the most relevant:

It takes a lot of paper

To gift-wrap an elephant.

The Dinosaur

The dinosaur had 2 brains —

One in his head

& small one in his tail,

So why did he fail?

Well,

Let me put a bee in your bonnet:

If you have a good brain,

Don’t sit on it.

A Poem on the Wrong Track

One day last winter,

A train caught cold

(It’s a true story,

Or so I’ve been told).

For one whole month

It stood in the rain,

Coughing & sneezing.

An achoo, an achoo, an achoo choo train.

Ping Pong Poem

pongpongpongpong

pongpongpongpong

pongpongpongpong

pongpongpongpong

pongpongpongpong

pongpongpongpong

pongpongpongpong

pongpongpongpong

pongpongpongpong

pongpongpongpong

pongpongpongpong

pongpongpongpong

pongpongpongping

Poinson Ivy

Personally

I think it’s silly

To always gather

Daffodillies.

What’s wrong with Poison Ivy?

We have barely scratched

The surface there!

Though once you have gathered

Poison Ivy,

You’ll be scratching everywhere!

Short Stories

Why Do Not I Play Golf

My Father, dressed in a brown suit, took a step forward and I ran to him. "Where's Janet?" I asked. I handed him my book bag. Then Mrs. Henry, my teacher, came over to me and asked, "Who is this?"

"This is my father," I told her.

"Then I guess it's all right," she said. Because of the bright sun, she held her hands over her eyes. My second grade teacher was an older woman with lots of gray hair, and the bright sun hurt her eyes. Many times she wore special glasses.

"It's all right," my father said. He took my hand and we walked out of the noisy playground toward his green and white Buick. He was in his late forties then, but he seemed to have the gait of a man much older. There was gray in his hair, but both Mom and I knew he had started to dye his moustache. "Janet was here," he said, "but I thought you would like to play some golf." He paused, looked at the sky, putting his hands over his eyes just the way my teacher had. "I paid her and told her she could have the day off."

I didn't say anything, but it sounded strange to me because my father hated to waste money. Janet was a high school student who looked after me until my parents got home from work.

It was Florida then. Perhaps as it is Florida now, but not the same Florida. The June sun was where it usually was, and the day was hot and humid. Someone had told me that it was the start of the hurricane season. Or maybe it was the end of the hurricane season. I can't remember which. After a certain age, our lives are mostly memory anyway. I climbed into the car. The seat was hot. My father tossed my book bag into the backseat. He didn't ask me about homework, so I didn't tell him. After all it was Friday. Even so, Janet would always ask me about my homework. Then Mom. Homework was useful because it gave everybody something to talk about. I had a lot of arithmetic homework that year, and my teacher wanted me to do it one way, whereas my father wanted me to do it another. For example, Mrs. Henry wanted me to use one line for each set of numbers. My father, who thought that was a waste of paper, insisted I should put two sets of numbers within each line. Then my mother would say something, and they would start to argue, while I sat at the kitchen table in tears. No wonder I wasn't getting good grades in arithmetic. Someone on the car radio sang "I was with you when you didn't have a dime."

"What about Mom?" I asked.

"What about her?" He aimed the car down Hollywood Boulevard. There was a small golf course on Johnson Street where we could always get on without any waiting. My father, who loved the game and played every Sunday, had some clubs cut down to my size. I played a few times but I wasn't very good at it. Still, it was something to do, something better than homework, and my father liked it if I came along. Sometimes he would find another person to play with and then I would just walk along and every once in a while hit a ball off the tee and then my father would pick it up.

For me, putting was the best part of the game. I was good at putting. I always spent the first fifteen or twenty minutes warming up on the putting green. The putting green seemed just right for players my size.

"How's Mom going to get home?" I asked.

"Someone will drive her home," he said. She always gets home, doesn't she?" There was something in his voice that I hadn't heard before, but I didn't have the vocabulary then to describe it. It wasn't right that he had come to pick me up, was it? And it wasn't right that he had left Mom without a ride. On the radio a black woman was singing "I hate to see that evening sun go down."

"I guess," I said. I wasn't quite certain that I wanted to play golf, but there I was stuck with the situation. "You don't have to work today?"

"I got out early," he said. Sometimes in summer the store downtown would close early on Wednesdays, but that was only in July and August. Besides, it wasn't Wednesday. It was Friday, and my father always had to work until nine o'clock on Friday nights. Both my mom and dad also had to work all day Saturday, too, and I had to go over to Grandma's house. I tell you, the weekends went by kind of quick. Sunday was the only day all three of us were ever together, and by Sunday I mean the afternoons, because in the mornings my father always got up to play golf, while Mom and I went to the Little Flower church. I don't know why we went to church. I guess it was something to do. I didn't know anything about God.

"Marciano's fighting tonight," I reminded him. I was looking forward to sitting with him on the big bed in my parent's room, listening to the fight on radio. It was just something we did together.

"I know." We stood in the parking lot of the Sterling Golf Course, and I waited for my father to take off his suit jacket, fold it carefully and place it in the trunk. Then he undid his tie. Then he pulled out a bright green knitted vest which he pulled over his shirt. Then he put on his golf shoes. I didn't have golf shoes. I played in my sneakers. But that was okay. I didn't use the right golf grip either. My father kept trying to teach me, but I didn't like linking my pinky fingers together and so I used my baseball grip, which would sometimes send my father off into a fury. He was not an easy man to learn things from.

Then out came the golf clubs. His bag and then my four clubs which I just carried. A driver, two irons, and a putter. It was enough. My father had promised me a golf bag, but he never got around to getting me one.

"Are we going to listen to the fight?" I asked. We walked into the clubhouse and signed the register. There were some men at the bar, but my father didn't know any of them. A woman nodded in our direction, but nobody said hello.

"We'll see," he said. If he had been my mother, he would have added, "If you finish your homework." But if there was one thing certain in the world, it was that he was not my mother. As far as I could figure it, mothers and fathers had little in common with one another. I was amazed they could live together in the same house.

We went outside and we played the putting green for a while. And then we teed off. It was a quiet day at the course, not crowded at all. For which I breathed a sigh of relief. I hated to play when there were other people right behind us. I hated especially the first tee when there would be strangers watching and then I wouldn't drive it right and I'd be embarrassed.

My father hit first, right down the middle of the fairway, a good distance. And then I hit. It was good because it was in the air and fairly straight. And then we played. My father let me keep score because it gave me something to do, and the adding up of the numbers was supposed to help me with my arithmetic. I believe I have already told you how Mrs. Henry was big on arithmetic that year.

After nine holes we went inside the clubhouse and got drinks. Salty Dogs. What they were were cokes mixed with milk. My father had an ulcer and so he drank a lot of milk. Decades later it would be revealed that milk, because of it acid, wasn't good for ulcers. But we can live our lives with only the knowledge that we possess at the time.

And then we played another nine holes. I was getting tired and so on the ninth hole, which was the water hole, I sliced three balls right into the pond. Only one of the golf balls was new. The others had cuts and nicks in them. Mulligans. I didn't know why they were called mulligans. I still don't know why. Is that what we call progress?

It was nearly seven o'clock, but the sky was still filled with a stubborn light. We walked into the clubhouse and ordered supper. My father had two gin and tonics. I had a hot dog and milk. I didn't like the hot dog and I didn't like the milk.

"Should we call Mom," I asked, "and tell her when we'll be home?"

"Later," he said. "I'll call her later."

"But she could be making supper for us," I insisted.

My father shrugged. "Then she'll have plenty to eat," he said.

I didn't think it was a nice thing to say, but I didn't say anything. After all, he was my father, and there was nothing I could do about that. He was in a rare mood all right. There was nothing I could do after that either.

"You and Mom have a fight?" I asked. It was the first thing that came to mind.

"No," he said. "I haven't seen her all day."

"I hope she got home all right."

My father didn't answer. He had ordered a platter of sweet sausages and mashed potatoes, but he hadn't touched the sausages. Maybe he thought the potatoes would be good for him. But, of course, he shouldn't have been drinking either. Not that he couldn't hold his liquor. One night I had seen my mother and two of her friends carrying my father home after he had bet a bartender he could drink ten straight vodkas and walk a straight line out the door. He drank the ten vodkas, walked out the door and collapsed in the parking lot. He was lucky. He could have killed himself.

"Why can't we go home?" I asked. I could hear myself whining. "I have homework to do." It was a Friday night. I never had done my homework on a Friday night before.

"What kind of homework?"

"I'm writing a story. I started it in school."

"What you got so far?" he asked, not looking at me, but looking at the television set over the bar. There was a jazz band playing. And someone else was playing a juke box. It seemed as if there were music everywhere. My father preferred jazz, especially Benny Goodman. I suppose he could have been a musician if he didn't have a family to support, but he never said much about it, just beat time on the table with his spoon.

"That's Martha Tilton singing," he said. Later he asked me, "You got it?"

"It's in the car."

"Go get it," he said. "I'd like to hear your story."

"No, you wouldn't," I told him. He held out the car keys and I took them from him. "You ought to wait until we go home and I finish it."

"Still a lot of light out," he said. "Time to play another round."

I didn't feel like playing another round and so I walked out to the parking lot and got the story out of my book bag. It was just a couple of wide-lined pages. I brought my homework back inside and sat down at the table. My father was still staring at the TV set.

"Find it?" he asked.

"Yes," I said. I sat down across from him. He had ordered me another Coke. Mom would have been angry. She didn't want me to drink so many sodas.

"Good. Read it to me."

I looked around.

"Don't worry. No one's paying attention. Everybody's too caught up in their own lives. You could be out of work, dying on the pavement, and they'd just step over you as if you were never there."

I didn't say anything. I tried to hold my pages up to the light. We had been studying insects in Mrs. Henry's class, and I had wanted to write a story about spiders, but it was difficult to think of anything to say. "Once upon a time," I read, "there was a castle called Beekman, and inside that castle was a king called Henry. Everybody called him Henry because he was the 7th king to be named Henry. At night all the people were afraid of ghosts. All the children were being told that there are no ghosts, even when the grown-ups were afraid.

"And one day the children woke up and their mother (Jane) came in and told them, John and Jody, that their father had died. The children looked sadly up at their mother; they weren't only unhappy because their father died, they were scared because their father might turn into a ghost. Then the King came in and said, ‘Jane, there is going to be a war. People will die.'

"After the war, 300,100 people died. When the King came back, he said, ‘I have good news. We won the war.' The End."

I had drawn some pictures of a man on horseback and soldiers and some bombs falling, but I didn't show them to my father. In truth, he didn't look all that interested.

My father rubbed his temples with his fingers. "How did you hit upon the number 300,100?" he asked. I shrugged. "I don't know."

"I bet you get an A on it. Sounds a lot like Hamlet." He finished and stood up. "Well, are you ready for another round?"

"Can't we go home? I'm tired," I said.

"Tired? How can you be tired? We only played eighteen holes. Besides," he added, "there's still plenty of light."

We went back onto the course. The sun was getting low in the sky. I gave my father my story and he folded it and placed it inside his golf-bag. This time, two old men and two old women were at the first hole. They looked so fragile; I thought that the slightest breeze would blow them over. Florida was full of old people. Because they were slow, they said, they allowed us to play through. I didn't like to have people watching me, so I topped my drive and it dribbled a few feet out in front of the tee. I walked out and got it and teed off again. I did the same thing again, but this time I just decided to play it. I had the feeling the people were laughing at me. My father hit a beauty of a drive, nearly 200 yards, right down the left side of the fairway.

After I took a 9 on the fourth tee, a short one, I decided to walk and to watch my father play. I thought my not playing would speed things up and we would get home in time for the Marciano fight, but my plan backfired. My father decided he wanted to practice his backspin and so he started to play a second ball. It didn't matter, because the foursome of old people were still stuck somewhere between the second and third hole. Slow was not the name of their game.

As he played into the clubhouse, with me pulling the golf-clubs on the aluminum cart, the sun was nearly gone. The sky had thin strands of pink a long way off.

"Want another hot dog?" my father asked.

"No." I said. "I just want to go home."

"Too early to go home," my father insisted.

"Are you kidding?" I asked. "What about the Marciano fight?"

"Forget the Marciano fight." He said. He ordered me a Coke a beer for himself. "There's more to life than listening to two men beat their brains out. Besides we can sit here and listen to it, if you want."

"They'll be closing soon."

"I don't think so."

"Don't you have work tomorrow?" I pleaded.

"No. I don't have to work tomorrow," my father said emphatically. He slammed his mug of beer onto the table. "And I don't have work the next day either. Or the day after that. I don't have to go to work again. We can live out here and play golf.

"What about Mom?"

"What about her?"

"She's probably getting worried about us."

"I called her."

"When?"

"When you went out to get your homework."

I stared at him, but I couldn't figure out if he was telling the truth or not. He was my father. Why would he lie to me?

"I think she'll still be worried." I said.

"I don't think so," he repeated. "When did anybody ever worry about me?"

"What did she say?"

"She said it was a Friday night. We could stay out and have fun."

"Really?"

"Really."

I just wanted to go home.

He ordered another beer. My heart beat loudly in my chest. I had my own medical problems. The doctor said I didn't have a regular heartbeat. I thought he had told my mother that I wouldn't have long to live, but maybe I was only imagining that. I guess so, because it turned out that I would live a lot longer than anyone thought. "We going home?"

"No. I want to play another round."

"Another round? We can't play another round. It's dark out."

"So what?"

"So we can't see where we're hitting."

"There's enough light."

"I don't want to."

"Just a few holes. We'll play on the back nine."

"I want to go home."

"Why? Home will be there whenever we get there. You don't have school and I don't have any work."

I hated when he said that. It made me very afraid. He was pulling the golf cart toward the tee for the 10th green.

"No. I quit. I didn't like it there anymore. I've got better things to do with my life than try to sell clothes to people who don't know anything about a good cut of cloth."

We took out some mulligans, golf balls he didn't care about losing. "Besides I can make more money at the dog track. I've got a system, you know."

I knew. I had seen him working on it almost every night. It involved a lot of arithmetic.

He hit the first ball off into the darkness. I didn't play along. I merely took the handle of the golf cart and pulled it along, pretending to be his caddie. We were the only ones on the course now. Except for five geese that had wandered over. It took a while to find the golf ball, but we found it. My father had a sense of where he hit it. Actually, it wasn't as dark on the course as I thought it would be.

"I'm getting chilly," I said.

"Take my sweater," he said. "There's a sweater in the golf bag."

"You carry everything in your golf bag," I told him. I didn't get the sweater and he didn't take it out for me. What he did take out was a flashlight. "You can hold this while I putt."

After he sank his putt, a 10 footer or so, I fished the ball out of the hole. The ball felt warm to my touch. "Why did you quit your job?"

"I don't know," he said, walking ahead of me. I pulled the cart. "You get older you get tired of things."

"What kind of things?"

"All kind of things. It's something you won't know about until you get to be my age." We stopped by the large white plastic balls that marked off the men's tee, and then a little farther on the woman's tee. When I first started to play golf, I had used the women's tee, but after a while I thought it was too embarrassing. That was the main trouble with golf – it was the most embarrassing game in the world. When I played baseball, even when I struck out with runners on base, I didn't feel nearly as stupid as I did when I missed a golf ball. There was, after all, in baseball a pitcher who was trying to get you out.

My father didn't tee off right away. He placed his ball upon a tee and then sat down to stare at it. He and I just sat on the wooden bench and inhaled the smells. There was something about the grass smells, the dirt smells, mixing with the warm summer air, that made me feel as if I were on another planet. I sat next to my father and felt embarrassed for him. Mostly I was frightened. If he didn't have a job, what was going to happen to us? Could we afford to do anything? Weren't we poor enough already? Hadn't Mrs. Henry given me the class Christmas tree to take home, perhaps thinking we couldn't afford our own tree. I hated that feeling, that we were so poor that we couldn't afford what my friends had. I mean it was pretty obvious to me that most of my friends had more money than we had.

We sat there for about twenty minutes not saying anything, not doing anything. The only thing I could think to do was to wash the golf-balls over and over and so I got up and did that. When I went into the golf-bag, I also took out the yellow sweater that was folded in there. Of course, it was much too long for me, but there was no one around to see.

Whoever invented the golf-ball washing machine must have been a real genius. You just lifted up this piece of wood, placed a golf-ball in a hole at the center, and then plunged it up and down several times in soapy water. Two brown soft wire brushes scraped the ball clean. There was a small white towel hanging by the post to dry the ball with. After I cleaned about a dozen balls, I placed them one by one into the golf-bag and sat back down.

"What time is it?" I asked.

"Why are you always asking what time it is?"

"It's getting late."

"Just a few more holes."

"You're going to lose all your golf balls."

"So? Who gives a shit." He stood up and approached the tee. I was surprised by his language. My father very rarely swore, at least when I or my two sisters were around."

"What about the Marciano fight? Can't we at least listen to that. I was looking forward to that."

"I was looking forward to a lot of things too," he said. "A lot of things. The best thing in life is not to get your heart too set on things." I watched as he hit one far and true. At least it sounded far and true. Who could tell in the darkness?

If it wasn't down the fairway, there would be no chance of us finding it. I turned the flashlight on and kept the light in front of him as we walked. He was playing his own private game, and I was being left out. Behind us, the lights of the clubhouse were gone. Just a few outside floodlights were on. The manager and cook and bartender had gone home. They were probably warm and cozy, listening to the prize fight. Everybody else had something to do.

My father, after much looking around, found the ball, hit, lost it, hit another one, lost it. When we approached the green, the sprinklers had been turned on. My father gave up trying to putt through the water.

He said, "I was just standing at the counter with a twenty-dollar bill in my hand when Judy came by, grabbed the money out of my hand to take it to the cash register. I mean that was it. I mean she couldn't wait two minutes for me to ring up the sale. I mean she's in such a rush to make five bucks. That's when I had it. I couldn't stand it any longer. I've had it up to here and I told them what they could do with their job and I walked out."

He played the next hole, much the same way. I figured that the sprinklers were on timers or that someone would have to come back to turn them off. Under the water nothing felt warm.

He played two more holes in the darkness, lost about six golf balls, got disgusted, gave it up, and we cut across the course toward the parking lot.

After getting into his street shoes and putting our clubs away, he turned on the Buick's engine so we could hear the final rounds of the Marciano fight. We were the only car left in the lot, and I wondered what my father would say if the police drove by to investigate. Perhaps they would get into a fight. The Brockton Bomber was whaling the daylights out of Ezzard Charles. Or at least it sounded that way to me.

"Maybe we should go home. Mom is probably worried…"

"Stop being a worry wart," he said. He lit a cigarette, crumpled up the empty pack and tossed it into the lot. He was the one we all thought was the worry wart. He leaned across me, opened the glove compartment and found another cigarette pack. Smoking certainly wouldn't help his ulcers.

"Stop playing with that thing, will you? It isn't a toy." He was referring to the flashlight that I still had with me. I had forgotten to put it back in the golf-bag where it belonged. What kind of man keeps a flashlight inside his golf-bag?

"Does Mom know that you quit your job?" I asked. I had meant to ask the question earlier, but I had let it slip.

"I don't know. Let's just listen to the fight," he said. "What difference does it make if she knows or not? She's going to find out soon enough, isn't she?"

I wanted to ask if he had really called her, but I let that one slip too.

Not talking to one another, we sat elbow to elbow, listening to the fight until the very end. My father lit one cigarette after another. Finally, Marciano was declared the winner, and, because there was nothing more to do, I guess, my father quickly backed the car out of the lot and on to the street. There was hardly any traffic. Nobody had any reason to go anywhere. Everybody was home listening to the fight.

"The last time anyone worried about me was when I was your age, when my father kidnapped me and carried me off to some religious cult in the hills."

Jesus, I thought. Now what? Was the liquor taking effect? I tried to keep my eyes on the road, in case there was a traffic problem.

"Why did he do that?" I asked. Perhaps if I kept him talking he would stay awake. He had never told me about that part of his life before. Whenever he talked about his father, my father would never fail to mention how strict he had been, how he would hit my father with anything that was at hand. Even an ax handle. I don't think my father loved his father very much, but I didn't know enough then to ask that question. I just took it for granted that children loved their parents because that's what you had to do. My feelings about my father were getting confused. Suppose he hadn't called my mother. She would be frantic.

"I had scraped my knee on a ladder in my father's barn," my father said after thinking for a while. We seemed to be stopped at a traffic light forever. "And the cut had become infected. That's why I keep telling you to keep your cuts and bruises covered. But my father had joined this church that didn't believe in doctors. They believed God healed everything, and so I was left in bed without any medical attention. Finally, when my fever hit 103, my mother insisted on calling a doctor. Before the doctor arrived, my father and his friends carried me off to the hills. I remember them setting me down in the middle of the ground and hundreds of people in white gowns standing around me, singing and praying. Finally, the sheriff found me. Mother had taken out papers against the church, and the sheriff told my father that if I died, he and all the members of the church would be charged with kidnapping and murder, and so I was finally brought back to town and taken to a hospital. I nearly lost my leg, though. I never forgave him for that," he said. Abruptly he took his eyes off the road and looked me square in the face. He looked very frightened. "See, kid, you're not the only one who's got stories. I've got stories that will turn your hair white. Let's go home," he said, freeing one hand from the steering wheel and touching me lightly on top of my head, while I turned the flashlight on and off, and on, as if I were signaling for help from a sinking ship.